Features

Cultivation

Production

Cannabis testing 101

Promoting a better understanding of the product testing process

May 4, 2020 By Max White and Annabeth Rose

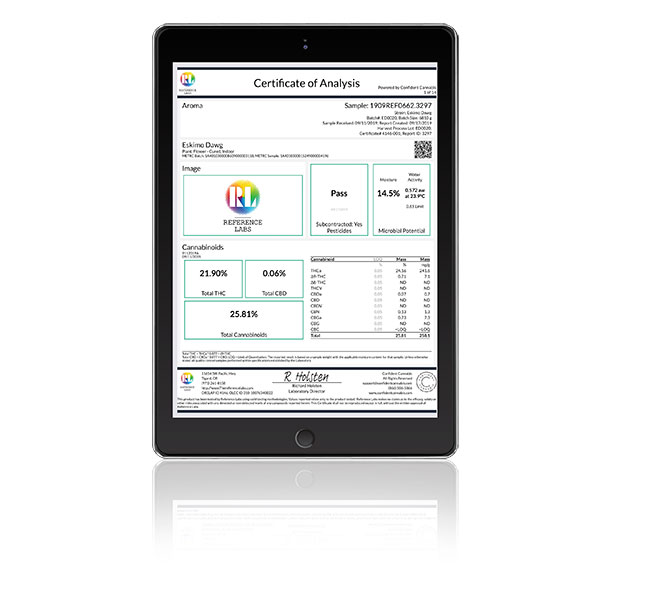

The certificate of analysis is essentially a report card that contains all compliant testing data required for a given sample batch.

The certificate of analysis is essentially a report card that contains all compliant testing data required for a given sample batch. Before the regulation of the cannabis industry, consumers would simply trust their “source” and fire up their organic bud grown with love. Depending on the grower, the flower may have been cultivated organically and free of pesticides and fungicides. Or, maybe not.

As the lucrative cannabis cultivation market grew in popularity and profitability, so did commercial cultivation practices. Today, we find ourselves in a significantly different industry, with hefty regulations and strict guidelines for what products producers can use on their cannabis crops. The cannabis industry, as a new and emerging market, can set the pace for a healthy approach to the cultivation of all crops, not just cannabis.

It has also been challenging at times. In California, as the recent legalization began to roll out, one out of five samples failed pesticide tests, according to a report from MJBizDaily. It has been a tight learning curve for cultivators to develop best practices under this newly regulated regime. This is why understanding the process for cannabis testing is critical for all licensed growers.

To provide growers a better understanding of the process of cannabis testing, we put together this “day in the life of a cannabis sample” to demonstrate this critical stage before cannabis products finally reach the market.

Sampling

All finished flowers are segregated into batches based on strain and harvest time. Everything is labeled and cured to market specifications. A sampling technician has acquired the sample of flower(s) to be tested and created a sample ID along with a photo. In Oregon, we used to be able to pick the kindest looking bud and turn that in for sampling. But now, samples are taken out of a 15-lb batch in a random grid selection method to obtain a sample that best represents the whole batch. It is similar in Canada, where a sample is randomly selected to ensure results that most accurately represent the batch as a whole.

Loss on drying

A portion of the sample initially collected is weighed wet and then dried to completeness to determine the loss on drying (LOD). This value factors into the final potency content. All samples are normalized to dry weight, removing the inconsistencies between samples due to their specific water content and results in comparable potency values across the board.

Potency

A sample of the cannabis product is extracted in a solvent, using various methods, so that the THC vacates the plant tissue (or extracted oil) and goes into the solvent solution where it can be further analyzed. A sample of that extracted solution is injected into a High-Pressure Liquid Chromatograph (HPLC) instrument that uses ultra violet (UV) light to detect the presence and concentration of the cannabinoids.

Pesticides

This process is crucial in guaranteeing that consumers and patients alike are consuming products free from harmful contaminants. At this stage, another sample of the cannabis product is extracted in a different solvent. This solvent pulls any pesticides from the plant material and into a solution that can be further analyzed. In most cases, the detection of all pesticides requires both a Triple Quadrupole Gas Chromatograph (GC-MS) and a Triple Quadrupole Liquid Chromatograph (LC-MS).

Potential errors in analysis

Ensure that you are using a lab that has educated and experienced technicians. Serious problems arise when unqualified staff in laboratories are not able to decipher the chromatogram (graphs) accurately. Some testing lab results we have received in the past failed for pesticides that have not even be used for that crop, all because of an internal laboratory error made by a technician while attempting to read the chromatogram.

Mold/mildew testing

The results of a total yeast and mold (TYM) test are an indication of yeast and mold contamination on a cannabis sample. This test is administered by counting the growth of colony-forming units (CFUs) from a cannabis sample when placed under specific laboratory conditions.

Yeasts and molds can cause deterioration and decomposition of foods, which is why food manufacturers will commonly test their products for TYM. However, TYM tests are unable to differentiate between pathogenic, beneficial, and benign yeast and molds, making them poor indicators of safety.

This is especially true in cannabis products, which has a diverse microbiome of beneficial microbes that are not harmful to humans. A low TYM result does not mean a cannabis sample is free of pathogens. A high TYM result doesn’t say a sample is harmful to consumers, either.

For example, many organic cannabis growers use Trichoderma, a fungus that can help with plant nutrition and protect it from disease. Some cannabis regulators require cannabis samples to pass TYM testing before they can be sold in dispensaries. The most current version of the Cannabis Inflorescence and Leaf monograph published by the American Herbal Pharmacopoeia, which many U.S. states use to determine pass or fail criteria for microbial testing, recommends less than 10,000 CFU/gram in cannabis plant material and 1,000 CFU/gram in extracts.

Heavy metal testing

Cannabis plants can absorb heavy metals from the soil and uptake of water. Some elements are toxic when consumed and pose health risks. Testing for elemental impurities (heavy metal testing) is required for fresh, dried and oil-based cannabis products.

The standard test includes four main elements: arsenic (As); Cadmium (Cd); Mercury (Hg); and Lead (Pb). Testing for heavy metals needs an Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) instrumentation and a validated method.

Creating a report

After all tests have been run, and the data is thoroughly analyzed, the laboratory director will look over the results to verify the data and ensure all results are within the laboratory’s accreditation standards. A certificate of analysis (COA) report is generated and will include all compliant testing data required for the corresponding harvest batch. This is the “report card” to the grower and will be attached, indefinitely, to the cannabis product as it travels through the supply chain.

Observation

There are plenty of reasons why testing is appropriate. There are some things about testing labs that can be hindering, however. First and foremost is that these labs are “for-profit” companies. In Oregon, in particular, that means some test results are modified so that the lab can please its customers and continue to gain business. It is not uncommon for farms to shop potency numbers. Which lab is currently giving away the highest THC numbers? Are pesticides being reported?

It’s getting better with time, but if one lab is dishing out high THC numbers, then farmers may sway that direction because we are also selling in a competitive market.

One solution might be a neutral, not-for-profit laboratory association – perhaps, state-run – that can perform the testing without a vested interest; then, convoluted test results might not exist.

In a privatized laboratory sector, the staff hired may or not be experienced in operating highly sensitive instrumentation, such as the LC-MS. If a chromatogram graph is misread, sometimes referred to as a false positive, a sample could fail compliance testing and cost the producer excessive time and money to fix before the product can go to market. One lab fails a sample while other labs pass the same sample. We have witnessed this anomaly multiple times. It is a frustrating situation and can put a sour taste in the community as to which lab can be trusted to produce accurate and reproducible results.

When the bottom line is profit, even laboratories that are responsible for creating report cards for public health and safety, make their own decisions on how to best budget their internal operations. In some cases that I have witnessed, this leads to cheaper, inexperienced staff and cutting of corners on quality control. As the market matures, we believe testing practices are leveling out, and better standards are being achieved. It takes patience.

Max White is the co-owner and director of cultivation at Aroma Cannabis in Portland, Oregon.

Annabeth Rose has a Bachelor’s in Cellular and Molecular Biology and a Master’s in Business Administration. She has been quality assurance director for several cannabis labs in Oregon.

Print this page